_Thanks to Jim, Ivan, Roy, Chris Hunt, Alex Stan, and the Asula team for discussion and review._

Blockchains are the home for crypto assets and tokenized forms of real-world assets, such as fiat-backed stablecoins. Beyond asset issuance and transfers, the most common activities that take place on blockchains are trading and lending.

The market structure for trading is generally well-understood; with open interest, volume, and order book data made publicly available across centralized and decentralized exchanges, the market can be analyzed well by its participants.

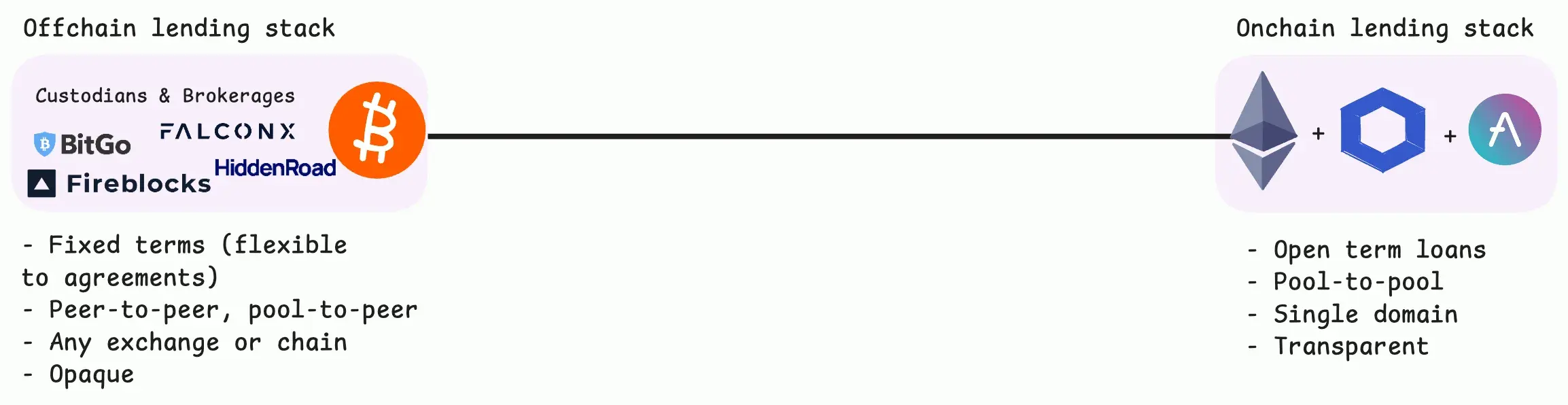

For lending, protocols like Aave and Spark that operate onchain are similarly transparent to trading markets. However offchain lending markets are less understood. Whereas CEXes provide a consolidated platform for trading, offchain lending activities occur in more bespoke, over-the-counter (OTC) agreements.

In this piece we take a comprehensive look at common lending activities and agreements in the market today. We explain fundamental counterparty and structural risks in the market, and discuss improvements to these risks to establish a more resilient crypto lending ecosystem. Specifically we discuss options for providing more operational tools and systems for transparency, as well as ways to elevate the role of onchain features in offchain agreements.

Overview

Institutions primarily access crypto through a traditional financial system overlaid on top of crypto assets, but without important infrastructure that enforces safer business practices. While traditional finance benefits from reporting standards and clearinghouses that track, net, and settle transactions between regulated counterparties, offchain crypto lending markets are fragmented across OTC desks without equivalent standards. Unlike onchain applications where transactions are verified on a public ledger, the offchain markets operate without similar systems of accountability. This also means that risk management is dependent on a lender’s proprietary systems rather than standardized industry practices.

As unprecedented institutional capital flooded the space during the 2020-21 bull market, the structure of crypto’s OTC markets was exposed as a critical vulnerability.

Recapping 2022

The Fed’s zero-interest rate policy after the 2020 COVID-19 crash created an environment of abundant, cheap capital, fundamentally altering lending desk incentives. With access to low-cost funding and pressure to generate yields in a zero-rate environment, lending desks began competing to capture market demand for leverage. Against the backdrop of bull market euphoria this led to increasingly relaxed underwriting standards. Three Arrows Capital (3AC) capitalized on this environment by taking out multiple undercollateralized loans from different lending desks to enter popular trades (like the GBTC premium trade) or yield strategies (like depositing in Anchor). When the GBTC trade became unprofitable and the Terra protocol imploded, a cascade of failures kicked off across lenders, many of which had over concentrated exposure to illiquid GBTC collateral, 3AC and/or other counterparties deposited into Anchor:

Fundamentally these bankruptcies were a problem of irresponsible lenders, with books that were overextended on short-term liabilities against collateral that was illiquid for longer durations.

Institutional Lending Today

Lending practices have sobered up since the bull market in 2021. Stricter risk management practices from leading desks has fostered a healthier, albeit smaller market. In contrast to its prevalence in 2022, undercollateralized agreements make up a smaller share of the current market. This also reflects a few key market constraints:

- Higher cost of capital: With the secured overnight financing rate (f.k.a SOFR, a benchmark for USD lending) around 5%, and lenders requiring an additional 2 to 10% (or more depending on the risk profile), returns for yield strategies are naturally compressed.

- Limited liquidity for scaling opportunities: Even when protocols or trading strategies offer attractive yields, they’re unlikely to be able to absorb significant capital without diluting returns.

- Fewer qualified borrowers: Stricter risk criteria likely has also reduced the pool of eligible counterparties.

We should note that we focus on these factors impacting the market for USD-denominated borrowing, whereas different dynamics exist for markets in other currencies (i.e. if borrowing ETH against stETH, the staking yields must eclipse the borrow rate for ETH against staked ETH).

Overcollateralized loans

Overcollateralized lending remains the focus for leading desks. As BTC and ETH are the most liquid crypto assets on the market, most agreements use these tokens as collateral. Fully-secured lending is simply more accessible for prospective lenders; the ability to find opportunities is no longer mainly a question of due diligence (though still a priority), but mostly a challenge of quality of collateral, cost of capital, and opportunity cost (depending on accessibility to other yield opportunities).

For bitcoin-secured lending, borrowers include individuals, crypto-native funds and regulated institutions, each of whom may access liquidity from different sources in the market:

-

For larger regulated institutions holding bitcoin, traditional banks have moved to support bitcoin-secured loans – for example, this summer Cantor committed $2B to bitcoin-secured lending. (Note this is different than an institution holding iBIT or other ETFs – they would use traditional securities-based loans)

-

For funds using a crypto-focused custodian, the custodian typically provides its own prime brokerage-like services; if it cannot directly lend from its own desk, they will connect clients with other lending desks.

-

For more active fund managers, custodial accounts at prime brokerages offer a suite of financial products with broader market access. The most common lending activities at these brokers target margin accounts for clients in their system, typically utilizing the broker’s own principal.

Loan Agreements

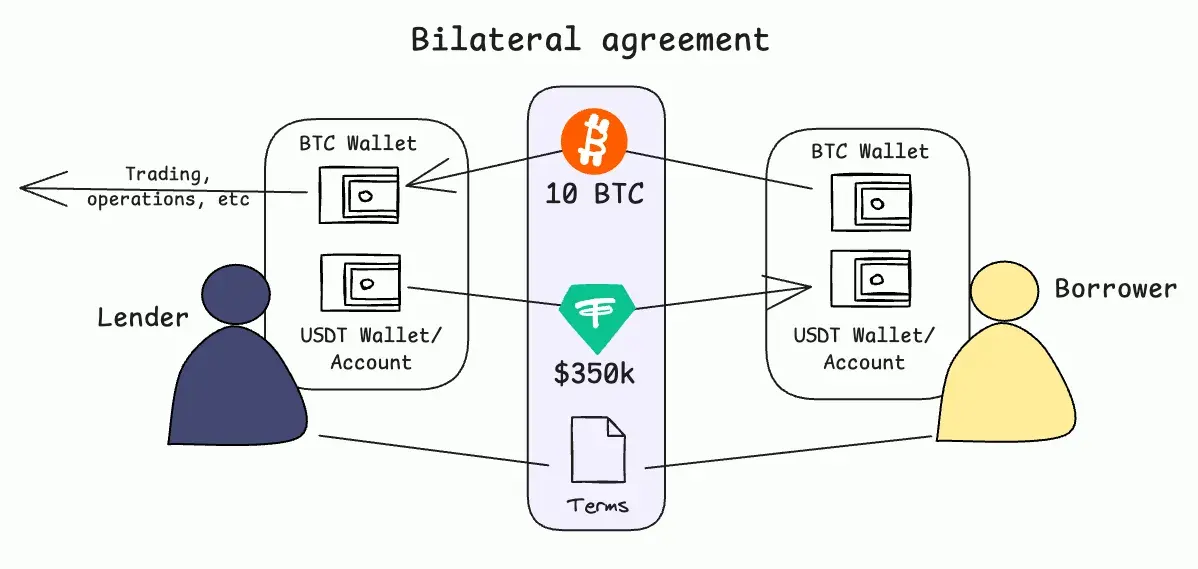

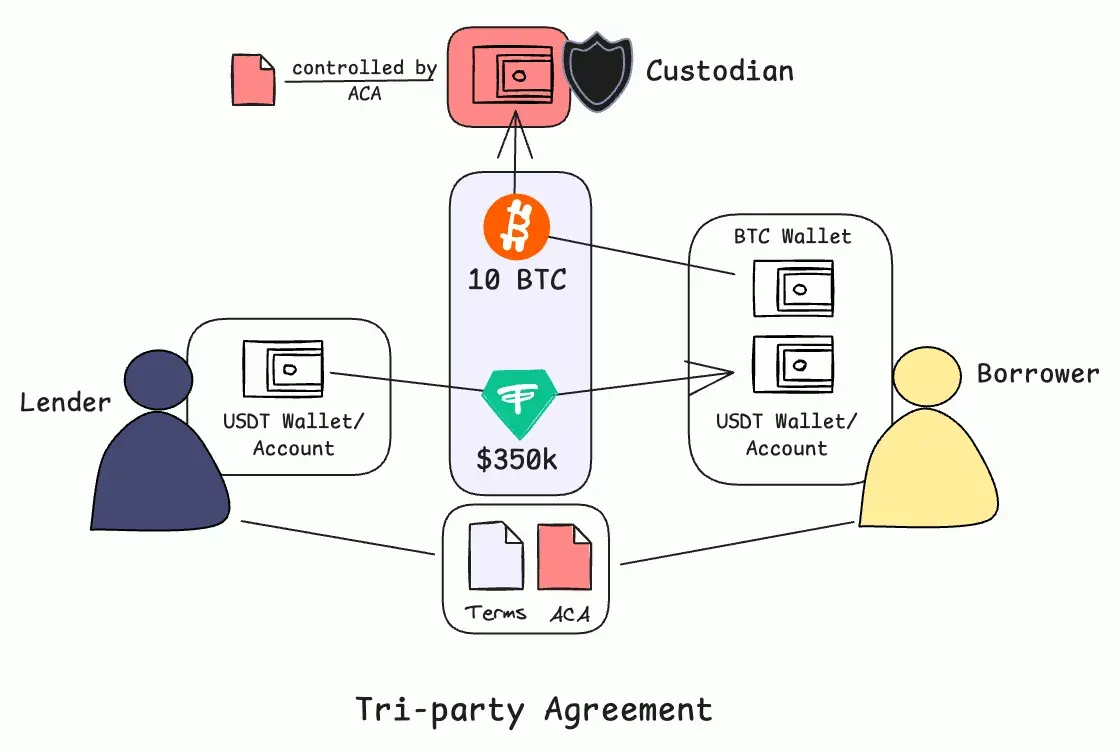

Engaging with any of the above-mentioned providers requires either bilateral or tri-party loan agreements.

In a bilateral agreement, both parties conduct an asset swap upon signing a loan agreement and terms. For example, for a 50% LTV loan, the borrower would send the lender’s address 10 BTC and receive 50% equivalent in USD in return. The terms of this agreement will specify the lender’s ability to use the BTC collateral they custody (in the below image the lender has no constraints). The agreement also includes the rate the lender charges the borrower and the repayment schedule of the loan, as well as other details.

In a tri-party agreement, the 10 BTC of collateral is sent to an escrow address managed by a third-party custodian. Control of the address is determined by an Account Controller Agreement (ACA). While this arrangement involves the overhead of engaging the third-party, leading custodians now offer bankruptcy-remote trusts with insurance coverage for the collateral. As a result these are typically preferred by more risk-averse borrowers:

Counterparty Risks

Counterparty risks are the risk that a participant on the other side of a financial contract cannot fulfill the terms of the agreement. These risks are apparent in any market, from complex derivatives to simple lending agreements. In our examples of bilateral and tri-party agreements, counterparty risk differs based on the perspective of the participants:

For borrowers in bilateral agreements in which rehypothecation is allowed, the borrower is exposed to the health of the lender’s balance sheet. In the event that the lender becomes insolvent, the borrower can become an unsecured creditor. If the collateral was used in agreements with other counterparties, recovery of the collateral asset in event of bankruptcy can be much more complicated.

For borrowers in tri-party agreements, counterparty risk is largely reduced since the collateral asset in custody lets them retain legal title to the asset (plus an insurance cushion), meaning their ownership of the asset is protected from insolvency of the counterparty.

For lenders in both bilateral and tri-party agreements, the primary risk is collateral liquidity; if the collateral cannot be liquidated in a certain time period, the lender can end up in a liquidity crunch across their book. Even with available buyers, poor liquidity can cause significant price impacts when liquidating – this explains why bitcoin is viewed as a high quality collateral asset for institutions due to its deep, 24/7 market liquidity.

Rehypothecation

This market structure in overcollateralized lending leads to more rehypothecation. This is the result of a relationship between capital efficiency and competitive pressures in the market:

- Overcollateralized loans are fundamentally less capital efficient.

- The market is highly competitive. Lenders must get creative to generate an edge and compete on rates.

- If they can offer better rates to other desks, they might capture a larger spread across their book, or they might meet more borrower demand. This can kickstart positive feedback loops if done sustainably, or spread bad debt in the system if done irresponsibly.

Higher rates from lenders (due to #1) leads a cost sensitive borrower to enable rehypothecation. Capital inefficiency comes at a cost, and many borrowers accept added risks from rehypothecation to avoid this cost. When rehypothecation is enabled, lenders can use collateral subject to terms they agree to with borrowers. They may also have relationships with separate trading desks that make use of the asset in yield strategies. Doing this successfully can supplement competition on rates (as in #2) and kickstart a feedback loop to attract more borrower deposits.

However with rehypothecation increasing exposure of the collateral asset to other market dynamics, any competitive advantage for the lender comes at the cost of increased risk.

What exactly is the cost of capital inefficiency?

If a borrower denies rehypothecation, the rate they are quoted can vary – today these rates can be as high as 15, even 20%. Quotes depend on different variables used to quantify the opportunity cost of supplying the loaned asset. For example, if the lender usually borrows capital at a cost of 8%, naturally any rate they charge for a no-rehypothecation agreement would need to exceed this. Conversely, this creates a trade-off for borrowers between bilateral and tri-party agreements: lower rates with increased risks, and better security at a higher rate.

Operational and Structural Risks

One result of this highly competitive, yet opaque market is that there is less information available on the overall health of the market to its participants. While the most active brokers & desks collect data, their own view of the market and participants (or eligible counterparties) can be different than their peers. As we’ll discuss in the next section, there is no incentive for them to share this information given information asymmetry in the market can supplement their competitive advantage.

This opacity also contributed to operational complexities for crypto lenders; there is less data available for any less-sophisticated participant to diligently underwrite counterparties. Additionally, maintaining proper collateral and position management for different counterparties often causes fund operations to splinter across multiple custodians, collateral management systems and other services providers.

Ultimately each of these factors has contributed to the market consolidating into a handful of sophisticated institutional liquidity providers, OTC lending desks, as well prime brokers that have the resources to manage these operations at scale.

This opacity and operational complexity is also indicative of deeper problems in the traditional market structure. Without a clearing layer to net and settle counterparty interactions, there is no system-level control to prevent bad debt from leaking into the broader market. For example, in the event of additional rate cuts or high yielding opportunities (both market conditions for more profitable lending activity) the market lacks a mechanism to deter more irresponsible participants or new entrants from supporting sub-optimal collateral assets or non-creditworthy borrowers.

Improving Resiliency in Lending

Thus far we have explored the various lending activities, agreement types, and risks of offchain lending markets in crypto.

Below we will explore the space for improving in this market. We break down improvements into two distinct approaches: the first is top-down, focusing on lenders opting in to more transparent standards today; the second is a bottom-up approach, focused on moving key processes to blockchains that have embedded systems for verifying accountability.

Standards for Transparency

Transparency in the market exists on a spectrum. On one side, we’d seek more radical commitments for transparency, leveling with standards common in trading markets that allow participants a more accessible, consolidated view of the market. Unfortunately this radical transparency is difficult to implement for offchain lending. These challenges arise from any of the following reasons:

- There is no consolidated venue from which borrowers & lenders match orders in offchain agreements.

- Services that facilitate matching are not incentivized to share comprehensive market data due to competition in the market.

- The same participants with comprehensive market data are also likely to be the most active in bilateral agreements, so sharing details on positions can be a competitive disadvantage.

- Even with a commitment to transparency, lending agreements are nuanced and include sensitive information. Standardizing a market that runs on nuanced agreements is difficult.

The other side of the transparency spectrum may be more feasible. Market participants can opt-in to use tools and services from third parties to share data on a bespoke basis, or provide their own proofs or attestations to supplement counterparty confidence. Using platforms like Credora, counterparties might use proofs to verify the value of assets or positions on CEXes and other platforms without exposing details of an activity or the composition of their exposure. This generally improves upon the operational complexity and embedded opacity in crypto lending. Though we should note that while it is growing in popularity today, this is still not a panacea for the market.

Moving from Offchain to Onchain

A more complete approach moves all financial contracts and services from offchain lending markets into onchain systems. This directly solves for the structural issues we highlighted above.

The risks inherent to offchain markets is a result of systems built to maintain accountability in financial contracts. If the contracts themselves are moved to systems built on cryptographic assurances, we graduate from bespoke, highly trusted methods for accountability to cryptographically verifiable standards for accountability.

More concretely, this can include moving the loan matching, risk monitoring and collateral management processes each into smart contract-run protocols. We can look at one instance of this for a collateral management system: a protocol can allow borrowers to define a fixed set of actions that control how collateral might be used, or it may automatically deposit the collateral to make specific trades or earn yield from various products. This is a relatively simple solution, but when applied in the context of our above discussion it materially elevates security of collateral assets in tri-party agreements by replacing the third-party custodian’s role with code from the protocol.

This offers Pareto improvements to the market, allowing lenders to earn from collateral usage with substantially less overhead, while borrowers have more visibility/control for counterparty activities with an improved rate. Though specifics here may prove challenging to implement in practice (for example, scaling would be constrained by onchain liquidity), this illustrates how traditional OTC agreements can be further improved when they’re integrated with smart contracts and protocol-run systems. One example of a protocol implementation with similar features would be Gearbox. Other teams are also working on more curated, KYC-only pools for regulated counterparties.

Implementation Challenges: Limits of DeFi Today

Today the largest crypto applications are lending protocols, collectively these control over $43B in TVL at time of writing. However by now we should know that offchain markets are unlikely to adopt more rigid and transparent systems given they are accustomed to more flexible and private alternatives. This directly contrasts with the smart contract systems of DeFi.

Improving offchain protocols with onchain capabilities requires us to first elevate DeFi to bridge this gap:

While today’s smart contract-based lending activity is constrained to pool-to-pool systems like Aave or Maker, more primitive DeFi infrastructure must adjust to incorporate the following features:

- Improve support for cross-domain lending. (e.g. use collateral asset A on chain X to borrow asset B on chain Y, examples include with Aave Portals or Stargate/Radiant)

- Expand market designs that reflect requirements from different lenders – for example, peer-to-peer, pool-to-peer, or peer-to-pool systems are underdeveloped in DeFi, though equivalents of these are most common in traditional practices

- Basic privacy support that is required for managing sensitive info between regulated counterparties

On the latter two points, we can reference a previous bedlam post that introduced ways to improve peer-to-peer lending by using order books; in this design protocols can enable more efficient matching while maintaining the benefits of pooled liquidity. Iterations on this architecture could introduce features that better integrate with institutional requirements, such as support for different collateral types or private matching for regulated counterparties on top of pooled liquidity.

The first point is especially important for Bitcoin-secured lending. As we discussed in our last post, the majority of Bitcoin-secured loans have been pushed into offchain markets. Here it’s worth reiterating the technical challenges underlying BTC’s dominance in offchain markets:

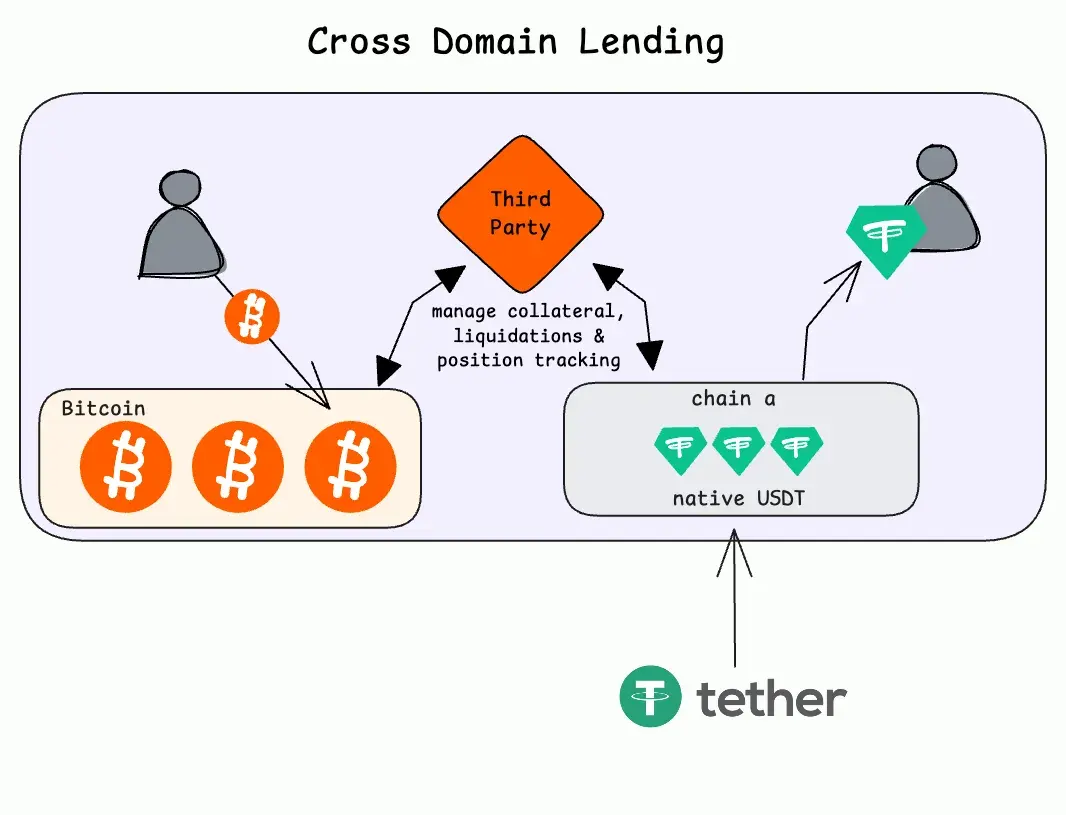

Because the Bitcoin network can only handle bitcoin transactions, any lender or application must deal with multiple domains when using bitcoin as collateral for borrowing assets that exist outside the network:

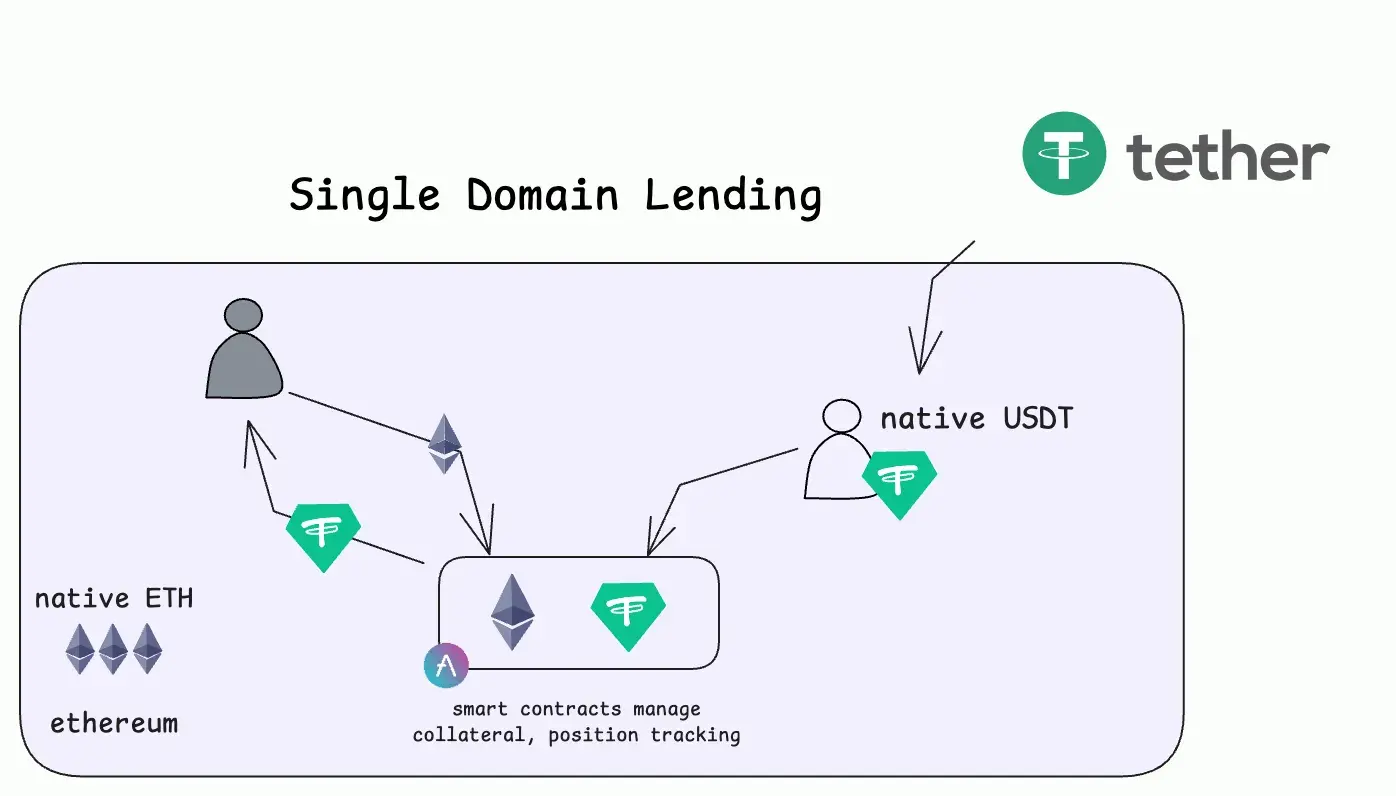

We can contrast this with classic pool-to-pool, single-domain lending, where both collateral and borrowed assets use the same blockchain environment. Here, a single smart contract system can manage these processes programmatically:

There are a number of teams working to solve these cross-domain lending challenges. Specifically for bitcoin, we’d expect programmatic collateral management, liquidation policies and other features which require more dynamic spending conditions to pose ongoing challenges, at least unless Script upgrades enabling covenants bring more expressive Bitcoin spending policies.

To conclude

The crypto lending market has evolved significantly since the failures of 2022, with institutions implementing stricter risk management practices and moving to predominantly overcollateralized arrangements. While this has established a smaller but healthier market, fundamental challenges remain around transparency and responsible capital efficiency.

The path ahead likely can take a more hybrid approach which combines the best aspects of both traditional and onchain markets. Although complete transparency may be difficult to achieve in offchain markets, further adoption of tools allowing for selective attestations can help build counterparty confidence. Furthermore, while DeFi protocols currently lack the flexibility and privacy features needed for institutional adoption, innovations in cross-domain lending and peer-to-peer architectures could eventually bridge this gap. This can be especially helpful in improving bitcoin markets, as more innovations improve on technical limitations that have contributed to the asset’s prominence in offchain markets.